Cybersecurity is Complex. Its UX Doesn’t Have to Be.

Cybersecurity is complex and constantly evolving. That fact isn’t going to change. But I think we can all agree that a complex user experience (UX) is far from ideal when asking employees and users to secure personal and business devices, accounts, and information. Security practices place a lot of emphasis on putting barriers and controls into place—as they should. Yet a great user experience is all about channeling the right behaviors (which, yes, sometimes means putting guard rails in place) with the goal of empowering users to be more secure. I’m not sure if that distinction is a meaningful one, but it’s a theme I’ve noticed and tried to unpack in this article.

If you’re in the business of creating new technologies or part of designing and implementing the security program at your organization, your technology skills far exceed the average person, according to an international study published in 2016 by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills). And that isn’t likely to change anytime soon. That’s not to say that the average person doesn’t take security seriously. According to our research, they try to do the right things to ensure their business and personal devices and accounts are secure. But, the reality is, keeping up with the latest technology advancements and improving digital hygiene aren’t on the average person’s list of top priorities.

Despite increasingly sophisticated technology, humans still play a significant role in ensuring security goals are met. No surprise there, right? At the organizational level, people set security goals and put controls (or don’t) in place. Employees must be aware of and abide by organizational policies. And both employees and consumers must have the awareness of and ability to manage and make decisions regarding devices, accounts, and data—even if significant controls are in place. For example, an individual must ultimately make the decision to click or not click the link in a phishing email.

While this is an oversimplification of the many moving parts that relate to cybersecurity, the key takeaway is that if people are a key component of keeping things secure, then it’s important to align security solutions with their behaviors, motivations, and goals. Developing solutions with the end user in mind means we are accounting for what users don’t know and helping them develop better habits and make informed decisions. It means optimizing the user experience for employees and customers when it comes to security. So what user experience practices can we apply to how we approach security?

First, a great user experience shouldn’t start with making assumptions about what the user knows. Any successful user experience requires user research: understanding the goals, motivations, and behaviors of end users. Part of that research is identifying and accounting for what the user knows and doesn’t know. We can’t possibly design effective solutions if we wrongly assume the user already starts with a body of knowledge or baseline of skills—a problem I see repeatedly in hardware and software UX and organizational policies. For example, how can we expect an employee to spot a sophisticated phishing email if they don’t know the basics of identifying one? Employee training is, of course, important in this situation. But instead of relying on well-intentioned-but-still-human employees to correctly identify all malicious emails, some email clients now alert users if a message seems suspicious. Instead of assuming the user already has the knowledge—or will always be extremely vigilant in what they click or tap—provide solutions to help put the odds in their favor.

If you’re building digital products, chances are you can provide experiences that both anticipate problems and provide solutions for them. For example, Gmail emails and/or texts users when a new device accesses the account and provides steps for securing the account if the access was not authorized. In fact, through user research, you may find that users will benefit from learning about cybersecurity best practices by using your digital product. Consider this an opportunity to nudge the user into making better privacy/security decisions.

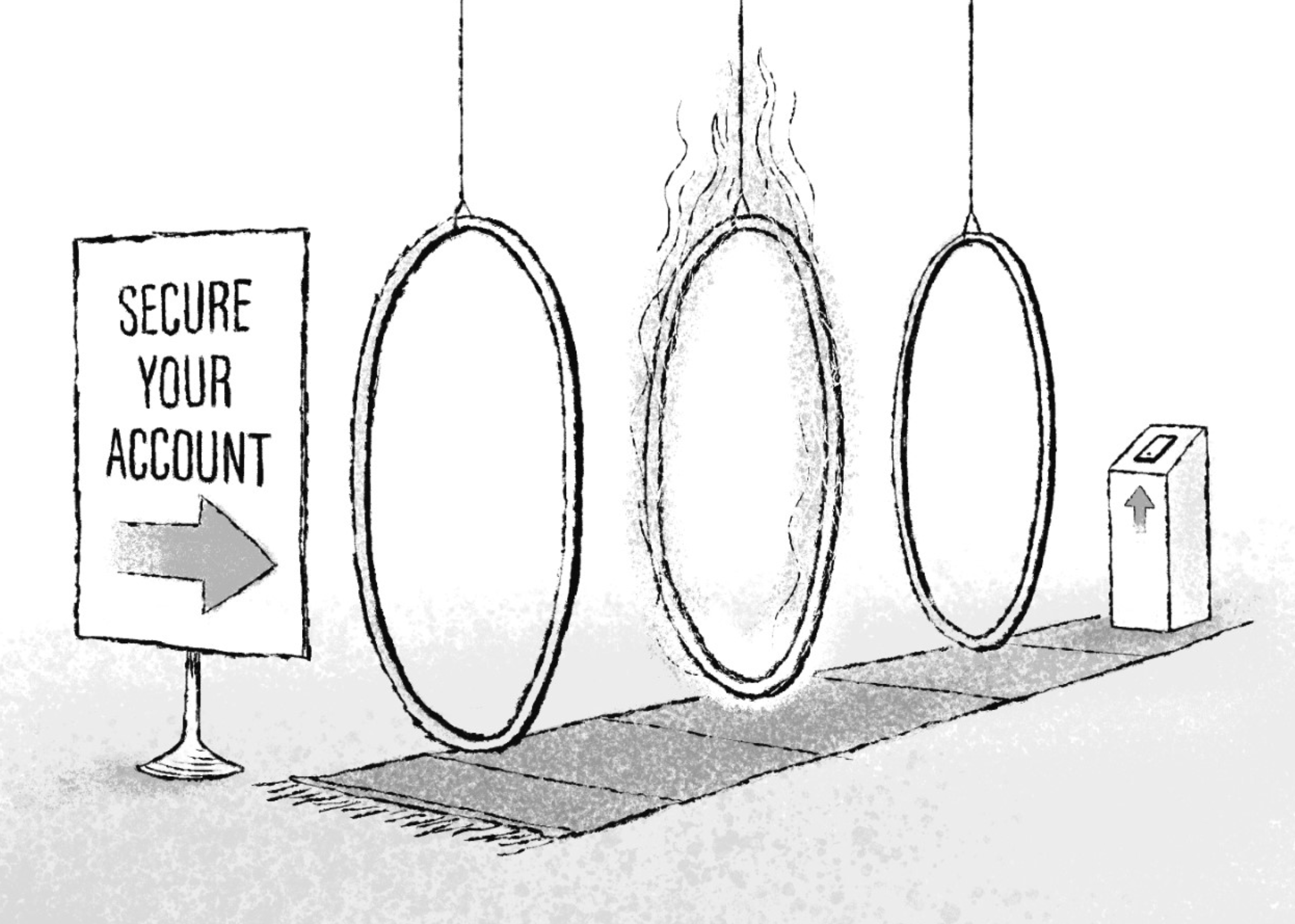

Second, a great user experience removes barriers or puts them in place depending on the circumstances. We want to make the user stop and think when an action may have irreversible consequences. For example, does the user really want to delete this critical file? In contrast, we generally want to remove barriers in helping users achieve a desired outcome. Recently a friend had to set up multi-factor authentication for a new account for her job. The accompanying instructions, supplied as a Word document with pixelated screenshots, were so confusing and complex that, had there been any way around it, she simply wouldn’t have enabled multi-factor authentication. That’s not the kind of experience that will encourage employees to comply with security policies.

Putting guard rails into place might mean building the security feature into the product or onboarding experience. For example, guiding users through changing default settings instead of assuming they know they exist or how to access them.

As with any user experience—and especially when it relates to security—resources are limited and not everything can be both urgent and important. Further, the security realm is increasingly complex. Teams can’t wave a magic UX wand and expect everything to be fixed. But, by thinking about end users as we develop new technologies and policies, we can educate users, encourage the behaviors that lead to good security practices, and help users when, inevitably, something goes wrong.

Have a technical team that are making UX decisions? Learn about our in-house (also remote) UX workshops.